It is imperative that value to the owner not be substituted for TCV (i.e. usual selling price or market value). In Rose Bldg Co. v. Independence Twp. 436 Mich. 620; 462 N.W.2d 25 (1990), the Michigan Supreme Court held:

The Constitution requires assessments to be made on property at its cash value. This means not only what may be put to valuable uses, but what has a recognizable pecuniary value inherent in itself, and not enhanced or diminished according to the person who owns or uses it. [Emphasis in original.]

Before a big box store’s usual selling price can be concluded, the identity of the interest in the property being appraised must be identified. Different interests in any given property can have significantly different values. Paraphrasing well-known author and real property appraiser David Lennhoff, “you can’t get the right value unless you value the right rights.”

This article focuses specifically on owner-occupied big box stores. Because the properties are owner-occupied, there is no lease in place and no leased fee interest. TCV for owner-occupied property is based on the fee simple interest in the property. Fee simple interest is defined as follows:

Absolute ownership unencumbered by any other interest or estate, subject only to the limitations imposed by the governmental powers of taxation, eminent domain, police power, and escheat. The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal (5th ed., 2010).

Thus, this article discusses the usual selling price of the fee simple interest in an owner-occupied large free standing store real property, unaffected by the person who owns or uses the property.

II. Big Box Stores Are All Built To Suit And Not Built To Thereafter Be Sold Or Leased.The above section of this article addressed the legal principles governing the TCV of big box stores and other types of property. This section addresses ways in which big box stores are factually unlike most property types. Big boxes are all built to suit or custom built for a specific retailer’s business. They are either constructed by (1) a retailer or (2) for a retailer pursuant to a pre-construction contract whereby the retailer agrees to lease the property after construction under terms that allow the contractor to recover its costs and profit. Unlike many property types (apartment complexes, shopping centers, warehouses, office buildings, houses, etc.), big box stores are never built for the purpose of selling or leasing after construction is completed.

Although this gets us ahead of the story, the question should be asked why, unlike many other property types, are big box stores not built to thereafter be sold or leased. The answer is quite simple. Big box retail stores are custom built to accommodate a particular user’s image and marketing strategies. For reasons discussed below, no one could reasonably expect to profit from custom construction of a big box store and thereafter selling or leasing it in the market.

Although an existing big box store is most often clearly suitable for retail use by another retailer, the market tells us a buyer of the fee simple interest in an existing big box store, at a minimum, is going to make substantial modifications to the property. One not familiar with sales of fee simple interests in big box stores will ask why after sale of the fee simple interest in a big box store are big box store buildings either demolished or substantially modified when the building was suitable, as is, for retail use. The answer is that each big box store retailer has its own business image and desired store layout and design - façade, flooring, lighting, location of restrooms, etc. Each big box retailer wants all its stores to look alike and not like another retailer’s stores.

In short, the market tells us that when the fee simple interest in an existing big box store is sold or leased, one of two things almost always happens - (1) the building is demolished or (2) the building is substantially modified.

III. Valuation Of The Fee Simple InterestBorrowing a quotation from the late William Kinnard, a professor, author, and well-known real property appraiser, “An appraisal is the logical application of available data to reach a value conclusion.” It is useful to keep this truism in mind when valuing property, including the fee simple interest in a big box store property.

A. Sales Comparison Approach.

In valuing the fee simple interest of a big box store by the sales comparison approach, ideal comparable sales are fee simple sales of similar properties, i.e. sales of the same interest in property as the interest in the big box store being valued.

The Michigan Tax Tribunal has consistently used comparable fee simple sales of properties that were vacant and available when valuing a subject big box store. See Home Depot USA, Inc. v. Twp. of Breitung, MTT Docket No 366428 (2012), affirmed by the Michigan Court of Appeals in an unpublished opinion, Home Depot USA, Inc., v. Twp. of Breitung, Michigan Court of Appeals Docket No. 314301, (April 22, 2014) (“Petitioner’s selected comparables were vacant and available at the time of sale. The Tribunal finds that these sales best represent the fee simple interest in the subject property. Vacant and available at the time of sale is not an alien term: an appraiser’s analysis of exchange value must account for this eventuality. Not all properties transition instantaneously from seller to buyer like a light switch. Moreover, vacant and available for sale does not automatically present a negative connotation.”) (Emphasis added.)

As the Michigan Court of Appeals further explained:

The tribunal properly valued the properties by valuing the fee simple interest of the properties as if they were vacant and available. By comparing the subject properties to similar big box retail properties that were vacant and available, with various adjustments made to compensate for differences between the properties, Allen [taxpayer’s appraiser] was able to determine what the fair market value would be of the subject properties, if they were to be sold in a private sale, as required by MCL 211.27(1). Therefore, Allen’s sales-comparison approach properly valued the TCV of the fee simple interest of the subject properties.

Home Depot USA, Inc., v. Twp. of Breitung, unpublished opinion per curiam of the Court of Appeals, issued April 22, 2014 (Docket No. 314301).

Below are some common issues and errors in concluding to the TCV of the fee simple interest in big box stores using the sales comparison approach:

1. Leased Fee Sales. A leased fee comparable may not be a valid indicator of a fee simple interest. Income producing real estate is often subject to an existing lease or leases encumbering the title. By definition, the owner of real property that is subject to a lease no longer controls the complete bundle of rights, i.e., the fee simple estate. The price paid for a leased fee sale is a function of the contract rent, the credit worthiness of the tenant, and the remaining years on the lease. If the sale of a leased property is to be used as a comparable sale in the valuation of the fee simple interest in another property, the comparable sale can only be used if reasonable and supportable market adjustments for the differences in rights can be made. The Appraisal of Real Estate, p. 323 (13th ed.); p. 406 (14th ed).

2. Sale - Leasebacks. Sale/Leasebacks are typically financing transactions and always transactions between related parties, i.e. in addition to seller and buyer, the parties are tenant and landlord to each other. Thus, a price paid for a sale/leaseback comparable sale is typically based upon a financial transaction not reflective of the fee simple interest value and is always a transaction between related parties.

3. Expenditures after sale. Misapplication of reimaging costs as “expenditures made immediately after purchase” results from failure to make a logical application of available data.

a. It is appropriate to adjust a comparable sale price for expenditures that “have to be made” when such expenditures do not have to be made for the subject property

b. It is not appropriate to adjust for expenditures made after the sale to “reimage” or customize the big box store for the buyer’s specific business purposes. An adjustment for a buyer’s expenditures after sale are erroneously included when the subject has the same or similar physical features and condition because both the comparable sale and the subject would typically be modified to satisfy the buyer’s business plan and image.

4. Zoning and Deed Restrictions. Real property in Michigan is restricted in use by zoning. Other means of restricting a property’s use also exist. One is deed restrictions. A deed restriction, like a zoning restriction, may have a negative effect on a property’s value. However, like a zoning restriction, a deed restriction may not affect a property’s value. Where a deed restriction exists on a comparable sale property, it is appropriate to determine if the restriction caused a diminution in price when considering using the sale as a comparable sale to value a subject big box store property. However, typically when big box stores sell with a deed restriction, the restriction is negotiated as part of the sale so as to not affect the buyer’s intended use of the property and does not affect the sale price for the property.

5. Highest and Best Use Issues. The highest and best use (“HBU”) of an existing owner-occupied big box store is likely going to be for retail use. In valuing big box store real property by the sales comparison approach, ideally each improved comparable sale would have the same or a similar HBU as the improved subject property. The Appraisal of Real Estate, p. 43 (14th ed. 2013). A big box store comparable sale not purchased for the subject’s same or similar HBU (retail) should be investigated to determine what evidence it provides about the value of the subject big box store property.

For example, if the improved comparable sale is physically comparable and suitable for retail use but the property sells for a use other than retail, the sold property’s HBU (as reflected by the sale) may not be even similar to subject’s HBU - retail. When that sale is used as a comparable sale without adjustment for this fact (but appropriate other adjustments), its use may result in overvaluation (but not an undervaluation) of the subject. If the comparable sale property suitable for retail use was offered for sale in the market and not bought for retail use, then the comparable property’s selling price for retail use (the subject property’s HBU) would have been equal to or less than its selling price for some other use - this is simply a logical application of available data.

B. The Income Approach.

The most contested issue involving the valuation of the fee simple interest in big box stores by the income approach is typically the determination of market rent. To the extent the Tribunal has relied on the income approach to value these properties, it has considered only arms length transactions between unrelated parties resulting in agreed upon rent for an existing building not rent for a non-existent store to be built to a tenant’s specifications. The subject of this article is existing big box stores and not stores to be built. Rental terms from build-to-suit leases and sale/leaseback transactions would not reflect market rent (except by accident). Similarly, landlord provided tenant improvements or tenant improvement allowances so the tenant can reimage or reconstruct space for its business purposes must be adjusted from stated rent for a rent comparable so that the concluded market rent is for the subject property as is (without additional rent that may be realizable by the landlord for providing for more than the subject property, e.g. a landlord provided tenant improvement allowance).

C. The Cost Approach.

1. The Cost Approach to value big box store properties is generally agreed to by appraisers to be inapplicable due to the fact that it is not used by buyers and sellers and because of issues relating to the quantification of total depreciation. If used, then replacement cost is the basis from which all depreciation must be deducted. Quantifying this depreciation including, proper functional obsolescence and external (economic) obsolescence determinations, typically must be done through information obtained through comparable sales and/or income approach:

2. Comparable Sales can be used to derive market extracted depreciation.

3. Income deficiency or capitalization of rent loss (the difference between rent at market and the rent required to justify investment based on cost new) can also be used.

Big box store real property TCVs are adversely impacted by substantial obsolescence. The question has been asked why do the fee simple interests in big box store properties sell for so little as a % of cost new? There are multiple explanations for this market fact which are generally applicable regardless of the property’s age:

a. All freestanding big box stores are custom built for the original owner’s business purposes and business model and the modified cost for a buyer’s business model/image is expensive.

b. Upon sale, at a minimum, there is modification for reimaging (when the building is not demolished). (Sometimes the modification is for a use other than retail.)

c. Fast growing e-commerce sales - In general, even big box retailers are not building new stores and when they are building, they are generally constructing smaller stores.

Significantly, the loss in value attributable to these obsolescence factors further explains why build-to-suit lease rental rates will typically be at rental rates above the market rental rate for an existing big box store property.

IV. Summary

In conclusion, the logical application of available data is required to answer the question: As of the valuation date, what is the usual selling price that would be paid for the fee simple interest in the subject existing big box store property?

The usual selling price is most appropriately determined from fee simple interest sales of similar existing properties and through market rent based on rents agreed to for other similar existing properties. The cost approach is generally not used. But when it is used, it would not likely provide a reliable result unless sales and/or income approaches to value are used to account for total depreciation.

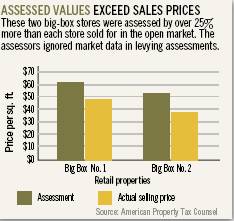

districts in Ohio and Pennsylvania can come in and file their own tax appeal to raise the value of a given property." Landlords must diligently review property taxes yearly, looking at assessments based on current marketplace ' conditions, Shapiro says. "My clients are fighting assessments," he said, "because assessors were ignoring the function obsolescence of their properties, which in some cases meant a 50 percent reduction in value."

|

|

|

|