As high-tech companies downsized in the US, their campuses were left with significant excess space.

"Therein lies the problem for property owners and tax assessors: What is the market value of these older high-tech campuses that were built without an exit strategy as single-user, special purpose properties?..."

In the 1970s and 1980s, the explosive growth of technology in the US touched off a construction frenzy of special-purpose, high-tech buildings in campuses designed for single users.

Dubbed flex manufacturing space, these buildings provided large floor plates to accommodate research and design, manufacturing and assembly, storage and distribution. Flex campuses came with fully integrated and interconnected utility systems, with office space typically arranged in what came to be known as cube farms.

These campus headquarters were built at a time when it was desirable and economically feasible for all of these functions to be under one roof, or one location, to facilitate internal communication, maintain control and security of specialized processes and promote internal efficiency.

By the early 2000s, however, demand for these sprawling hightech campuses declined. It became more cost effective to move manufacturing and assembly functions overseas and to reduce transportation costs by locating near emerging global markets. As high-tech companies downsized their operations in the US, their campuses were left with significant excess space.

Therein lies the problem for property owners and tax assessors: What is the market value of these older high-tech campuses that were built without an exit strategy as single-user, special purpose properties? An investigation into the market value of one of these campuses must begin with an analysis of the property's highest and best use.

There are only three scenarios for highest and best use of any improved property, and they are (a) continuation of the existing use; (b) conversion to an alternative use; or (c) demolition of the improvements and redevelopment of the site. A single property may also incorporate some combination of these alternatives. What follows are key points to consider with each approach.

Continuation of existing use. This valuation scenario assumes the owner would be selling or leasing excess space. There may be legal prohibitions and physical limitations to this alternative, however. Although communities embraced these campuses for the jobs they brought to the local economy, zoning ordinances enacted to establish these projects often contain provisions insuring that the properties maintain their campus-like setting, including limitations on ingress and egress, the percentage of accessory uses not directly connected to the high-tech use, signage and parking ratios that are inconsistent with a multi-use property. Frequently, utilities, security systems and the physical configuration of the campus are interconnected, making it impossible to convert the property to a multi-use or multi-tenant facility. In some cases, it is not financially feasible for the owner of a hightech campus to sell or lease excess space because the revenue generated from a sale or leasing would not justify the expense required to convert to a multi-use facility. These costs include tenant improvements, separate metering of utilities and leasing costs. Thus, the excess space becomes functionally obsolete and it is more cost effective to let it go dark.

Converting to an alternative use. An owner/user could consider vacating the entire campus and selling it on the open market. However, potential users for these types of properties are limited due to the property's excessive size (typically 700,000 to two million square feet), age and condition, large floor plates, outmoded technology and lack of demand due to globalization. A campus property may sell if the price is low enough to justify a significant expenditure in converting the campus to an alternative, multi-tenant use. In 2007, for example, real estate developer Benaroya purchased Microchip Technology Inc.'s wafer manufacturing facility, a 700,000-square-foot, 10-building campus in Puyallup, WA, for $30 million, far less than Microchip's asking price of $93 million. Thereafter, Benaroya reportedly invested $45 million to convert the facility into a multi-tenant, state-of-the-art business and technology center. Today, a significant portion of Benaroya's renovated facility remains vacant. Thus, the financial feasibility of converting a high-tech campus property to an alternative use is problematic.

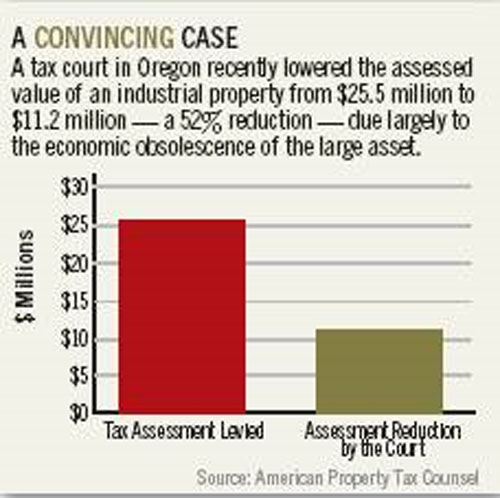

Demolish the improvements and redevelop the site. Because the previous two alternatives may not be legally permissible, physically possible or financially feasible, a number of large high-tech campus properties have been shuttered or demolished. Reported examples are Motorola's manufacturing plant in Mesa, AZ, and IBM's research park in Poughkeepsie, NY. For these reasons, high-tech campuses have been described as white elephants. Their current use is no longer in demand, and they are not suitable for conversion to an alternative, or second generation, use. The valuation and the assessment of these campuses must account for their inherent functional and economic obsolescence, which directly affect their market value.

The business value reflects all the factors of production —— land, buildings, machinery and equipment, skilled labor, managerial expertise and goodwill. It is incumbent upon owners to show assessors how to separate the value of the real and personal property from the value of the business for assessment purposes.

The business value reflects all the factors of production —— land, buildings, machinery and equipment, skilled labor, managerial expertise and goodwill. It is incumbent upon owners to show assessors how to separate the value of the real and personal property from the value of the business for assessment purposes.