Minnesota Supreme Court affirms decision barring use of airport concession fees in income-based property valuation.

A recent Minnesota Supreme Court ruling requires tax assessors to exclude an airport's concession fees from rent-based valuations for property tax purposes. The case offers a flight plan to lower taxes at many of the nation's transportation hubs, and underscores the importance for all taxpayers to exclude business value from taxable property value.

Every major airfield collects fees from food and beverage providers, retailers, banks and other businesses that provide goods or services on airport property. Concessionaires commonly pay these charges in addition to rent owed for the real estate where they operate. Many of these businesses are also responsible for property tax that passes through to tenants in a commercial lease.

The cases leading up to the March 29 state Supreme Court decision involved two car rental companies that challenged their 2019 tax assessments, claiming the assessor's office had overstated their property values by including the concession fee in its income-based valuation.

High-flying fees

Both Enterprise Leasing Co. of Minnesota and Avis Budget Car Rental pay a concession fee equal to 10 percent of gross revenues in addition to real estate rent for their operations at Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport. The tax assessor for Hennepin County had historically valued the auto rentals for property tax purposes by including the concession fee in its income-based approach to valuation.

The auto rental companies challenged the valuations on their 2019 taxes in the Minnesota Tax Court. Law firm Larkin Hoffman, which represented both taxpayers, argued that the concession fees are not rent and should not be included in the income approach for property tax purposes.

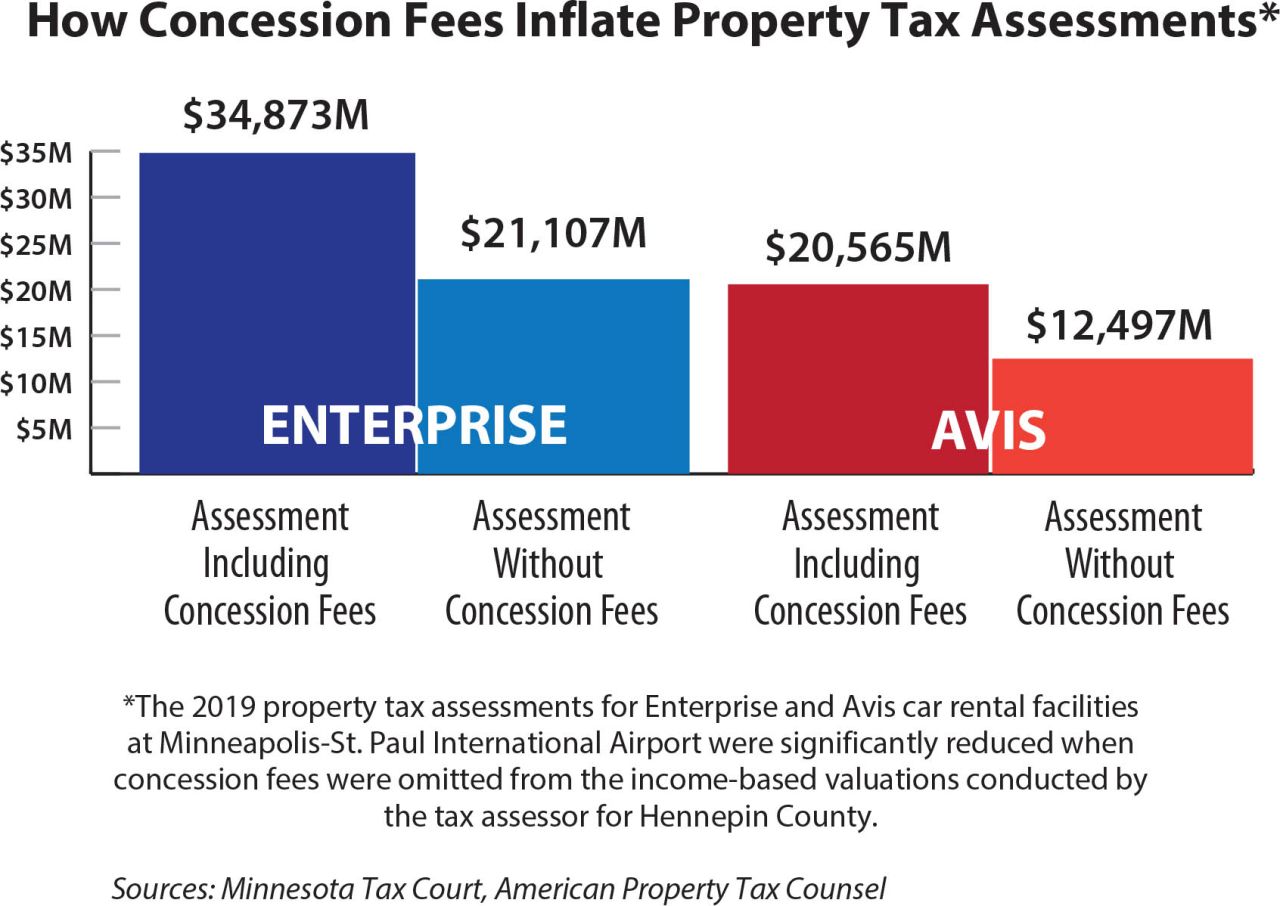

The rental agencies prevailed in tax court. The court found that the concession fee is not real estate rent and that the county substantially overstated market values by including the fee in its calculations. Correcting the assessor's calculation reduced Enterprise's value from $34.873 million to $21.107 million, or 39 percent less than the initial assessment. Avis' property value dropped 39 percent as well, from $20.565 million to $12.497 million.

The county appealed the tax court's decision to the Minnesota Supreme Court, arguing that the concession fee is rent that must be used in the income approach. The Court affirmed the lower court's decision, however, holding that "the concession fee is not rent for purposes of the income approach."

Fee-simple principles

The rental agencies' case stood on fundamental precepts of fee-simple valuation. Minnesota is a fee-simple property tax state, meaning valuations for property tax purposes must value all property rights as though they are unencumbered.

Additionally, the leased-fee interest, or landlord's rights subject to contractual terms, should not be used for property tax valuations. Per the state Supreme Court, rents attributable to specific leases are disregarded except to the extent they represent market rent. It follows that business income should not be included in valuations for property tax purposes.

Taxpayers doing business at airports across the country often pay concession fees or other charges based on their revenues or business performance. Many states, like Minnesota, require those same properties to be valued on a fee-simple basis, which should neutralize any impact of business value.

In representing the rental car agencies at all stages of their appeal, Larkin Hoffman stressed the importance of these valuation concepts and how the very definition of a concession requires its exclusion from calculations of taxable property value. A concession is a "franchise for the right to conduct a business, granted by a governmental body or other authority," according to the Dictionary of Real Estate. Accordingly, if a concession fee is a payment for the right to conduct business and not for the right of occupancy, then it is a business revenue.

The county argued that because the rental agencies' concession agreements included the phrase for "use of the premises," then the concession must only be for the real estate. However, the tax court found that the concession fee was consideration for access to the airport car rental market rather than the real estate.

The tax court reasoned – and the Supreme Court affirmed – that the concession fee was not for the real estate because:

Concession fees were also paid by off-airport rental car companies, indicating that the fee is a business revenue rather than rent;

Inclusion of the concession fee in the income approach would inflate the value to 10 times greater than the cost approach, which would be clearly unreasonable; and

Inclusion of the concession fee in the county's income approach distorted other inputs.

It is well established that a fee-simple property tax valuation should exclude business value. Now, Minnesota courts have also acknowledged that when a concession fee is for the privilege of accessing the airport market rather than for the real estate, that fee represents business value.

To prevent erroneous inclusion of business value, and since airports are special-purpose properties, the court gave primary weight to the cost approach. With this decision, Minnesota's highest court has confirmed that concession fees are not rent for real estate and instead represent business value that should be excluded from the income approach.

For taxpayers in any jurisdiction that taxes property based on its fee-simple value, the recent decision is a reminder to ensure that assessors are excluding business value when calculating taxable property value. For businesses that also pay concession fees in addition to rent, the Minnesota case may provide an impetus to learn how those fees affect their own property values. And if those inquiries spur taxpayers to appeal their assessments, then the Minnesota case law may provide a valuable example and support for their arguments.