By Cris K. O'Neall, Esq., and Michael T. Lebeau, Esq.1, as published by IPT May 2011 Tax Report, May 2011

On January 6, 2011, the Assessment Appeals Board in Orange County, California issued a significant decision for owners and operators of assisted-living facilities, particularly facilities dedicated to providing "memory care" services. In a nutshell, the Board found that a significant portion of the assessed values enrolled by the Orange County Assessor's Office for memory care facilities acquired in 2007 included the value of non-taxable intangible assets and rights.2 The Board's decision not only demonstrated the correct handling of intangibles under California's property tax statutes, case law and State Board of Equalization guidance document, but also found that the cost approach should be used to extract non-taxable intangibles from business enterprise purchase prices in order to arrive at values for taxable real and personal property.

The Nature of Memory Care Facilities

Memory care is one of the fastest growing segments of the assisted-living care industry. Memory care facilities specialize in the housing and treatment of persons suffering from senile dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and similar "memory loss" maladies. Persons with these conditions typically suffer from moderate to severe memory loss. Consequently, the nature of the facilities that house persons with these conditions and the operation of those facilities differ from most other types of assisted-living facilities and operations.

In order to protect patients or residents from leaving the facility unattended or unescorted, memory care facilities incorporate design features which are not typically found in other types of assisted-living or even convalescent care facilities. The facilities must be laid out so that residents can be observed continually, and so that they do not wander away from the facility by themselves. Points of egress must be limited in number and must be designed to allow electronic monitoring at all times. Despite these severe design restrictions, the families of residents housed in memory care facilities usually want such facilities to have the ambience of a residential or home setting.

The operation of memory care facilities also requires significantly more staffing than the typical assisted living care facility. This includes additional nursing staff as well as staff to observe and work with residents.

There must be sufficient staff to monitor residents at all times in order to insure that they do not leave the facility unattended. In addition, because residents are typically ambulatory, a variety of planned on-site and off-site activities are usually provided to them, which requires a larger number of employees. This higher level of service requires a resident-to-staff ratio that is up to twice that for general assisted-living facilities, and a more skilled, better trained, and more highly paid management and employee staff than is typically found in other assisted-living situations.

Treatment of Intangibles under California's Acquisition-Based Property Tax Regime

California's Proposition 13 made acquisition prices the touchstone for taxable value in many instances. However, Proposition 13 did not explain what to do in those situations where an acquisition price includes a business enterprise comprised of real property, personal property and intangible assets and rights. Fortunately, California Revenue and Taxation Code sections 110(d)-(f) and 212(c) explain that intangible assets and rights are not taxable, and the values of identified intangibles must be excluded from the value allocated to a business enterprise in order to arrive at the value of taxable real and personal property. This is confirmed by published appellate court decisions such as GTE Sprint Communications Corp. v. County of Alameda (1994) 26 Cal.AppAth 992 as well as by the California State Board of Equalization's guidance in Assessors' Handbook Section 502, "Advanced Appraisal" (1998), Chapter 6, pages 150-165 ("Treatment of Intangible Assets and Rights"). Similarly, California Property Tax Rule 8(e) (18 Cal. Code Regs., § 8(e» requires that where a property is valued using the income approach, "sufficient income shall be excluded to provide a return on ... nontaxable operating assets."

Purchase Transaction Created Challenges for Purchaser

In early 2007, a number of memory care facilities and operations in several states, including four facilities and related operations in Orange County, California, were acquired by a large assisted-living facility operator.

The acquisition included not only the real and personal property at the four Orange County locations, but also the government-issued facility operating license, existing workforce, and business operating at each site. While the real and personal property were subject to property taxation, the purchaser contended that the facility operating licenses, workforce and other business-related assets (contracts, relationships, etc.) were not taxable under California law.

The transaction documents for the 2007 transaction did not assign a specific value to the various categories of assets (real property, personal property, and intangibles) for each of the Orange County locations. Fortunately, the seller of the properties had commissioned an appraisal for each of the properties.

Those appraisals were provided to the buyer, however, they were of limited utility in the property tax context because they were "going concern" appraisals which determined a business enterprise value for each facility and, therefore, included a value for all property at each of the Orange County facilities that encapsulated real and personal property as well as non-taxable intangibles. Furthermore, the buyer had used the going concern values shown in the appraisals as the basis for reporting the acquisitions to the Orange

County Assessor's Office and the Assessor's Office had simply enrolled the reported values as the taxable value for each property. Thus, there was a clear "chain" of documentation showing that the Assessor's Office had enrolled the value of all property, including intangible assets and rights, as the taxable value of the property at each facility.

The situation was further complicated by the fact that the purchaser had acquired the intangible assets (namely the operating licenses) through a saleleaseback arrangement and not through the purchase and sale agreement by which the real and personal property were transferred. This was done because a considerable amount of time is usually needed to transfer memory care facility licenses to a new owner, and waiting for the licenses to be transferred would have delayed the transaction for a year or more. Use of the sale-leaseback arrangement was typical in the industry, and had facilitated the transaction. The buyer's representative testified at the Assessment Appeals Board hearing that the buyer would not have acquired the four Orange County properties without the facility operating licenses as it would have taken too long to go through the process of obtaining new licenses. However, because the licenses had not transferred with the purchase and sale agreement, it created an impression that the buyer had not acquired the licenses, which were perhaps the most significant intangible asset in the transaction. On a positive note, the purchaser was helped by the fact that the seller's purchase appraisals exhibited the extreme disparities between the assessed values enrolled by the Assessor's Office (based on the income approach values) and the purchaser's values which relied on the cost approach: the Assessor's values were as high as $500 per square foot, several times the buyer's values for real property; the Assessor's values were also more than twice the cost new without depreciation for the improvements; and the Assessor's values were based on net income figures the majority of which were unrelated to the real estate at each location. All of this served to demonstrate that the Assessor's values subsumed the value of non-taxable intangible assets and rights in violation of California property tax law.

Cost Approach the Key to Taxable Values

The purchaser used the cost approach as the basis for proving the value of the taxable real and personal property. The purchaser retained the seller's appraiser, who had prepared the appraisals used to establish and allocate the total purchase price paid for all of the acquired facilities, to testify at the Assessment Appeals Board hearing. The appraiser explained that the appraisals were going concern appraisals, and for that reason the income and sales comparison approach values in those appraisals represented business enterprise values or the values of the going concern operating at each location.

The buyer's appraiser also testified that only the cost approach conclusions in the appraisals would represent the value of the taxable real and personal property. In support of this, the appraiser relied upon the Appraisal Institute's text The Appraisal of Nursing Facilities (J. Tellatin, 2009), particularly the portions of that text stating that "property tax assessments should exclude the value of intangible assets" and identifying intangible assets to include operating licenses and assembled workforce (pages 37, 40, 314, 315). The appraiser also focused the Board's attention on two key passages from the Appraisal Institute's text: The greatest usefulness of the cost approach could be in allocating the total assets of the business to real estate, tangible personal property, and intangible personal property assets under the theory that the value of an asset cannot exceed the cost to replace it in a timely manner, less reasonable amounts of depreciation. (Page 284)

When the depreciated cost of the tangible assets and the land are less than the overall business enterprise value, the cost approach can be a proxy for real estate value. (Page 315) These conclusions were supported by portions of the California State Board of Equalization's Assessors' Handbook Section 502 at page 159, note 126, and page 163: "The cost approach does not typically capture the value of intangible assets and rights because the appraisal unit only includes the subject property." With this background, the purchaser's appraiser demonstrated that the cost approach values in his appraisal report for each of the four facilities represented solely the values of the taxable tangible real and personal property.

The Assessment Appeals Board's Decision

The Orange County Assessment Appeals Board upheld the buyer's values, with adjustments for increased land values and minor increases in construction costs to account for inflation. The Board supported the buyer's position that the intangible assets and rights, particularly the operating licenses, had transferred along with the real and personal property as part of the same transaction: 42. The Board finds that the purchase agreement, the master lease, the sublease and a financing agreement that were all part of the same transaction, within the meaning of California Civil Code section 1642, and the purchase price did reflect and include intangible assets which are not subject to taxation.

Critical to this finding was testimony by the purchaser's representative that the payments under the lease agreements were not based on market rates, but were related to financing the transaction. In fact, evidence presented to the Board showed that the amount of each facility's lease payment exceeded or nearly exceeded the total revenue generated by each facility. Civil Code section 1642 provides that "several contracts relating to the same matters, between the same parties, and made as parts of substantially one transaction, are to be taken together."

The Board also ruled that the cost approach was the proper method for valuing the properties because it excluded the value of intangible assets and rights: 43. The Board finds that the cost approach is the most accurate measure of accurate [sic] value since the comparable sales approach and the income approach both captured the value of the property as a going concern and that it includes the value attributable to nontaxable assets and rights. Hence, the Board utilized the [cost approach portions of the] appraisals submitted by the Applicants as a starting point for its valuation analysis.

The Orange County Assessment Appeals Board's decision to use the cost approach, and to reject the income approach and sales comparison approach values from the buyer's going concern appraisals, affirmed Assessors' Handbook Section 502's counsel to avoid use of going concern appraisals (page 157) and to rely upon the cost approach when other approaches cannot segregate the value of taxable real and personal property from the value of intangible assets and rights. The Board's decision is a clear statement of the correct approach to be applied in the multi-facility purchase context in order to exclude the value of intangible property and determine the value of taxable real and personal property.

1. The authors acknowledge Max Row of Complex Property Advisors Corporation in Southlake, Texas and David H. Fryday of Tellatin, Short & Hansen, Inc. in Salem, Oregon for their comments and input to this article.

2. The facilities are owned by NorthStar Realty Finance.

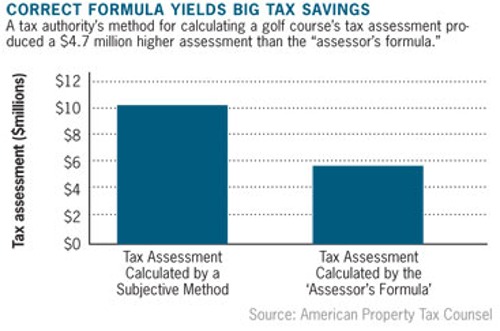

One prominent Long Island club recently sold to a developer. Another declared bankruptcy, and surviving golf courses are fighting to avoid similar fates. Closures outpace new openings as demand for golf declines and revenue growth remains flat in the face of rising costs especially property taxes.

One prominent Long Island club recently sold to a developer. Another declared bankruptcy, and surviving golf courses are fighting to avoid similar fates. Closures outpace new openings as demand for golf declines and revenue growth remains flat in the face of rising costs especially property taxes.