"The first thing any taxpayer needs to know to determine if they want to appeal their taxes is whether a reduction in assessed value yields tax savings. In states that place no limits on the amount of tax increase possible, owners can be certain that reduction in assessed value will generate a tax savings. However, several states' laws require the taxes rise by only a limited percentage in a given year."

By J. Kieran Jennings, Esq., as published by Affordable Housing Finance, Summer Special Edition 2007

Affordable housing owners looking for ways to save money and eliminate non-productive overhead should start by examining their property taxes. That doesn't require taxpayers to become experts in real estate tax law; they need only a working knowledge of the issues to identify when or if should hire an expert .

The basic issues

The first step in this process is to learn how assessors determine property taxes. One of the main indicators of fair market value that assessors use is the income that could be produced from the property using current rents, vacancies, and market expenses. In most states, real estate assessments are based on some percentage of a property's fair market value. Most often, the actual taxes are calculated using a millage rate (for example, $.001) multiplied by the assessment.

Right now owners of affordable housing face unprecedented increases in fuel and utility costs. And, because net income is a key indicator of market value, an increase in operating expenses likely causes a decrease in value. That means an owner's property might not be worth what the taxman says it is, and an appeal may be necessary.

Where does the taxpayer begin?

The first thing any taxpayer needs to know to determine if they want to appeal their taxes is whether a reduction in assessed value yields tax savings. In states that place no limits on the amount of tax increase possible, owners can be certain that reduction in assessed value will generate a tax savings. However, several states' laws require the taxes rise by only a limited percentage in a given year. In such states, a complex analysis is required to determine whether a reduction in assessed value actually results in a tax savings. This type of analysis calls for the skills of a property tax professional.

Some states' assessments may be based on ratios sometimes known as sale ratios or common-level ratios. In states such as New Jersey and Pennsylvania, an assessment may have originally been based on 100 percent of the appraised market value of the property, but over time that 100 percent assessment no longer reflects market value. So, at regular intervals, each county in these states conducts a study comparing the sale prices of all properties sold in a given period with the last assessed value of these same properties. For example, if the assessed values of properties sold for an average of 50 percent of the sales prices of those same properties, then the sales ratio for that period of time will be 50 percent for all properties in the municipality. This ratio then is used to convert the assessed value back to market value. Owners will want to track down the current-year ratio percentage and then review their assessment to ensure that the correct ratio has been applied in developing their assessment.

Finally, many states establish predetermined ratios. Ohio, for instance, places its predetermined ratio of assessment at 35 percent of the appraised market value every year in all counties. Assessed market value is determined by dividing the assessed value by the ratio percentage. As an example, a $35,000 assessment divided by 35 percent yields an assessed market value of $ 100,000, which then can be compared to the actual fair market value of the property. If the assessed market value appears to be higher then the actual fair market value (what a willing buyer would pay a willing seller in an arm's length transaction), then the taxpayer should consider contesting the assessment.

What can taxpayers do when over-assessed?

If you determine that your property has been over—assessed, file an appeal to reduce your real estate taxes. In some states, that will mean filing a formal complaint by a particular date. In other jurisdictions, the filing deadline depends on the mailing date of the assessment notices. Some jurisdictions mandate that parties must appeal their assessment within 15 days of receiving notice. If the deadline passes, in most jurisdictions, the taxpayer is prohibited from contesting their taxes until the following year. It is, therefore, imperative to know the local rules.

How does the taxpayer prove the case in an appeal?

As with every aspect of assessment law, proving the case varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Most typically, an appeal that has merit can be proven with a qualified appraisal. However, the rules regarding how that appraisal is prepared can vary from state to state. For instance, some states mandate that actual income and expenses be used to determine the market value of the property. In other states, an appraiser or property owner must prove the value based on unencumbered market conditions. An unencumbered market condition exists when a property built under Sec. 42, with a majority of its rents restricted, is appraised as if the property were conventional apartment. However, a property that enjoyed greater occupancy or rents because of Sec. 8 rent subsidy may be able to use a lower income figure based on prevailing market conditions. The income approach to value represents the common thread across exists the country for establishing market value.

Must an attorney file a property tax appeal?

Rules governing appeals vary greatly from state to state. In most states, an attorney is not required to file an appeal at the local level, but an appeal in court almost always requires an attorney. However, in a number of states, the courts have determined that the filing of property tax appeal is the practice of law, requiring an attorney

What risks and benefits come with contesting taxes?

Risks come into play when the appeals process is poorly handled, as that can impair a taxpayer's ability to reduce a property's value to its proper level in the future. Evidence poorly presented often remains in the record and is not retractable. Furthermore, in several states and with increasing frequency, school districts participate in the appeals process. In those states, the hearings may put the taxpayer at risk for an increase in assessment, if such is warranted.

The benefits of controlling real estate taxes far outweigh any risks involved, and by spending a little time learning the process, taxpayers can all but eliminate those risks. A newly established assessment often forms the basis for future assessment. Thus, a reduced tax this year positions an owner for future years because tax increases compound over the years. Even if assessments steadily climb in future years, having started at lower base can save money indefinitely.

Keeping real estate taxes and all non-productive expenses down becomes crucial to the economic health of an affordable housing property.

J. Kieran Jennings, partner at Siegel Siegel Johnson & Jennings Co., LPA, with offices in Cleveland and Pittsburgh. The firm is the Ohio and Western Pennsylvania member of the American property Tax Counsel, the national affiliation of property tax attorneys. He can be reached at kjennings@siegeltax.com.

J. Kieran Jennings, partner at Siegel Siegel Johnson & Jennings Co., LPA, with offices in Cleveland and Pittsburgh. The firm is the Ohio and Western Pennsylvania member of the American property Tax Counsel, the national affiliation of property tax attorneys. He can be reached at kjennings@siegeltax.com.

Not only are the rents affected by the first-generation tenant, the capitalization rate is significantly lower than market rates. The net-lease market into which these properties are sold is among the most active and developed in the real estate market, allowing for substantial liquidity, efficient pricing, and tax deferral through 1031 exchanges.

Not only are the rents affected by the first-generation tenant, the capitalization rate is significantly lower than market rates. The net-lease market into which these properties are sold is among the most active and developed in the real estate market, allowing for substantial liquidity, efficient pricing, and tax deferral through 1031 exchanges.

The business value reflects all the factors of production —— land, buildings, machinery and equipment, skilled labor, managerial expertise and goodwill. It is incumbent upon owners to show assessors how to separate the value of the real and personal property from the value of the business for assessment purposes.

The business value reflects all the factors of production —— land, buildings, machinery and equipment, skilled labor, managerial expertise and goodwill. It is incumbent upon owners to show assessors how to separate the value of the real and personal property from the value of the business for assessment purposes.

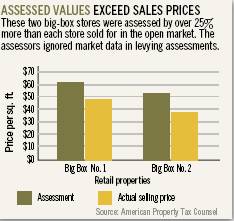

Just because your local assessor relied on comparable sales to give your property a higher valuation and a bigger tax bill doesn't mean you should pony up without a fight. Take a look at the comps and see how comparable they really are: You may be able to successfully argue that properties built recently, featuring larger unit sizes, or selling with Effective local tax assumable financing were able to fetch much higher sales prices than your property rates are a critical could reasonably command.

Just because your local assessor relied on comparable sales to give your property a higher valuation and a bigger tax bill doesn't mean you should pony up without a fight. Take a look at the comps and see how comparable they really are: You may be able to successfully argue that properties built recently, featuring larger unit sizes, or selling with Effective local tax assumable financing were able to fetch much higher sales prices than your property rates are a critical could reasonably command.