Rather than simply redevelop existing buildings to suit their needs, the build-to-suit model calls for the development and construction of new buildings that match the trade dress of other stores in a national chain. Think CVS pharmacy, Walgreens and the like...

The build-to-suit transaction is a modern phenomenon, birthed by national retailers unconcerned with the resale value of their properties. Rather than simply redevelop existing buildings to suit their needs, the build-to-suit model calls for the development and construction of new buildings that match the trade dress of other stores in a national chain. Think CVS pharmacy, Walgreens and the like. National retailers are willing to pay a premium above market value to establish stores at the precise locations they target.

In a typical build-to-suit, a developer assembles land to acquire the desired site, demolishes existing structures and constructs a building that conforms to the national prototype store design of the ultimate lessee, such as a CVS. In exchange, the lessee signs a long-term lease with a rental rate structured to reimburse the developer for his land and construction costs, plus a profit.

In these cases, the long-term lease is like a mortgage. The developer is like a lender whose risk is based upon the retailer's ability to meet its lease obligations. Such cookie-cutter transactions are the preferred financing arrangement in the national retail market.

So, how exactly does an assessor value a national build-to-suit property for tax purposes? Is a specialized lease transaction based upon a niche of national retailers' comparable evidence of value? Should such national data be ignored in favor of comparable evidence drawn from local retail properties in closer proximity?

How should a sale be treated? The long-term leases in place heavily influence build-to-suit sales. Investors essentially purchase the lease for the anticipated future cash flow, buying at a premium in exchange for guaranteed rent. Are these sales indicators of property value, or should the assessor ignore the leased fee for tax purposes, instead focusing on the fee simple?

The simple answer is that the goal of all parties involved should always be to determine fair market value.

Establishing Market Value

Assessors' eyes light up when they see a sale price of a build-to-suit property. What better evidence of value than a sale, right?

Wrong. The premium paid in many circumstances can be anywhere from 25 percent to 50 percent more than the open market would usually bear.

Real estate is to be taxed at its market value — no more, no less. That refers to the price a willing buyer and seller under no compulsion to sell would agree to on the open market. It is a simple definition, but for purposes of taxation, market value is a fluid concept and difficult to pin down.

The most reliable method of determining value is comparing the property to recent arm's length sales, or to a sale of the property itself. It is necessary to pop the hood on each deal, however, to see what exactly is driving the price and what can be explained away if a sale is abnormal.

Alternatively, the income approach can be used to capitalize an estimated income stream. That income stream is constructed upon rents and data from comparable properties that exist in the open market.

For property tax purposes, only the real estate, the fee simple interest, is to be valued and all other intangible personal property ignored. A leasehold interest in the real estate is considered "chattel real," or personal property, and is not subject to taxation. Existing mortgage financing or partnership agreements are also ignored because the reasons behind the terms and amount of the loan may be uncertain or unrelated to the property's value.

Build-to-suit transactions are essentially construction financing transactions. As such, the private arrangement among the parties involved should not be seized upon as a penalty against the property's tax exposure.

Don't Trust Transaction Data

In a recent build-to-suit assessment appeal, the data on sales of national chain stores was rejected for the purposes of a sales comparison approach. The leases in place at the time of sale at the various properties were the driving factors in determining the price paid.

The leases were all well above market rates, with rent that was pre-determined based upon a formula that amortizes construction costs, including land acquisition, demolition and developer profit.

For similar reasons, the income data of most build-to-suit properties is skewed by the leased fee interest, which is intertwined with the fee interest. Costs of purchases, assemblage, demolition, construction and profit to the developer are packed into, and financed by, the long-term lease to the national retailer.

By consequence, rents are inflated to reflect recovery of these costs. Rents are not derived from open market conditions, but typically are calculated on a percentage basis of project costs.

In other words, investors are willing to accept a lesser return at a higher buy-in price in exchange for the security of a long-term lease with a quality national tenant like CVS.

This is illustrated by the markedly reduced sales and rents for second-generation owners and tenants of national chains' retail buildings. Generally, national retail stores are subleased at a fraction of their original contract rent, reflecting pricing that falls in line with open market standards.

A property that is net leased to a national retailer on a long-term basis is a valuable security for which investors are willing to pay a premium. However, for taxation purposes the assessment must differentiate between the real property and the non-taxable leasehold interest that influences the national market.

The appropriate way to value these properties is by turning to the sales and leases of similar retail properties in the local market. Using that approach will enable the assessor to determine fair market value.

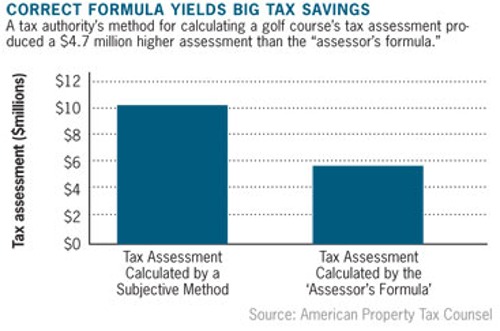

One prominent Long Island club recently sold to a developer. Another declared bankruptcy, and surviving golf courses are fighting to avoid similar fates. Closures outpace new openings as demand for golf declines and revenue growth remains flat in the face of rising costs especially property taxes.

One prominent Long Island club recently sold to a developer. Another declared bankruptcy, and surviving golf courses are fighting to avoid similar fates. Closures outpace new openings as demand for golf declines and revenue growth remains flat in the face of rising costs especially property taxes.