States moving to address proper valuations of LIHTC projects

"The cost approach calculates the expense of replacing a building with a similar one. That doesn't work in this context because without the tax credit subsidy, LIHTC projects could not be built in the first place..."

An unfair property valuation by a local tax assessor can cripple the operation of a low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) operation. Unfortunately, the inconsistency and uncertainty of how assessors value completed developments is a common impediment to financing LIHTC projects.

Without guidance at the state level, local assessors may value projects without consideration of the regulations that encumber the property and limit its income producing potential. Tax assessments based upon the highest use, rather than the actual use, of the property can even prevent development altogether.

The majority of states base their property tax valuations on fair market value. Typically, assessors value real estate by one of three methods—the market approach, the cost approach, or the income approach—and each presents challenges in relation to LIHTC assets.

The market approach of analyzing comparable sales is difficult to apply because there exists no market of tax credit property transactions to rely upon.

The cost approach calculates the expense of replacing a building with a similar one. That doesn't work in this context because without the tax credit subsidy, LIHTC projects could not be built in the first place.

The income approach is generally favored when valuing income-producing property, such as an apartment building that generates a cash stream of paid rent. However, conflict exists over whether to value the property based upon estimated market rents or the actual restricted rents that are inherent in an LIHTC operation.

For example, in New York, just as in many states, there existed no clear statutory guidance or case law to provide a uniform method of assessment for affordable housing. Many times assessors took the position that these properties should be assessed on an income basis as though they operated at market rents. The result was inflated property tax bills based on market rents that LIHTC projects cannot charge due to rent restrictions.

State legislation has slowly matured in this area. In 2005, New York became the 14th state to address the proper valuation of LIHTC properties. Other states that have passed legislation adopting a uniform method of assessment include Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Utah, and Wisconsin.

New York's Real Property Tax Law directs local assessors to use an income approach that excludes tax credits or subsidies as income when valuing LIHTC properties.

To qualify, a property must be subject to a regulatory agreement with the municipality, the state, or the federal government that limits occupancy of at least 20 percent of the units to an "income test." The law requires the income approach of valuation be applied only to the "actual net operating income" after deduction of any reserves required by federal programs.

The New York statute is representative of other states, such as California, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, and Nebraska.

Maryland's tax code states that tax credits may not be included as income attributable to the property and that the rent restrictions must be considered in the property valuation.

Likewise, California mandates that "the assessor shall exclude from income the benefit from federal and state low-income tax credits" when valuing property under the income approach.

However, there are still many states without legislation, leaving the valuation of these projects to the whims of a local assessor who may not understand the intricacies of an LIHTC project.

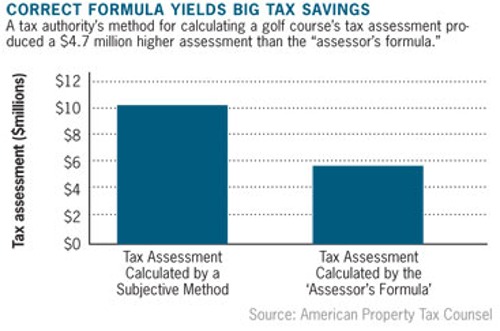

One prominent Long Island club recently sold to a developer. Another declared bankruptcy, and surviving golf courses are fighting to avoid similar fates. Closures outpace new openings as demand for golf declines and revenue growth remains flat in the face of rising costs especially property taxes.

One prominent Long Island club recently sold to a developer. Another declared bankruptcy, and surviving golf courses are fighting to avoid similar fates. Closures outpace new openings as demand for golf declines and revenue growth remains flat in the face of rising costs especially property taxes.